Endurance athletes consistently strive for performance enhancement, aiming to be stronger, fitter, and faster. Traditional endurance training is characterised by a large volume of steady-state training, but incorporating speed work into an endurance athlete's regimen can provide a robust stimulus for significant gains in performance. So, let's unpack the ways endurance athletes can ‘up the ante’ using speed work.

Speed work involves short, high-intensity efforts, with long recovery periods, targeting the anaerobic energy system. This differs from traditional endurance training, which primarily targets the aerobic energy system. While endurance athletes indeed need a well-developed aerobic base, neglecting the anaerobic system can limit performance.

Incorporating speed work enhances both aerobic and anaerobic capacity. It improves VO2max, the maximum amount of oxygen an athlete can utilise during intense exercise, and lactate threshold, the point at which lactate begins to accumulate faster than it can be cleared from the bloodstream. These adaptations enable athletes to maintain higher speeds for longer durations.

Speed work also enhances neuromuscular efficiency. Fast movements necessitate the recruitment of fast-twitch muscle fibres, which are often underutilised in traditional endurance training. Developing these fibers enhances muscle power, translating into greater force production, higher speeds, and improved economy.

Despite its benefits, speed work must be approached strategically to minimise the risk of injury and overtraining. Following are key principles that endurance athletes can use to incorporate speed work effectively.

-

Gradual Incorporation: It's essential not to rush into speed work. Instead, gradually incorporate speed training, starting with just one session per week. As the body adapts, athletes can add additional speed sessions, ensuring they have ample recovery between each.

-

Specificity: Each speed session should be specific to the athlete’s event. For example, a marathoner might focus on running intervals at their goal race pace, while a cyclist might incorporate high-intensity interval training (HIIT) to mimic the surges in power necessary in road races.

-

Periodisation: Incorporate speed work into a periodised training plan. This means focusing on speed work during specific phases of the training cycle, rather than maintaining a constant emphasis on speed. This approach ensures athletes peak at the right time, while also avoiding burnout and injury.

-

Active Recovery: The rest periods between speed intervals are not an opportunity to sit down and catch breath but should include active recovery. Light jogging or cycling helps to flush out lactate and speed up recovery, ensuring athletes are ready for the next bout of speed work.

-

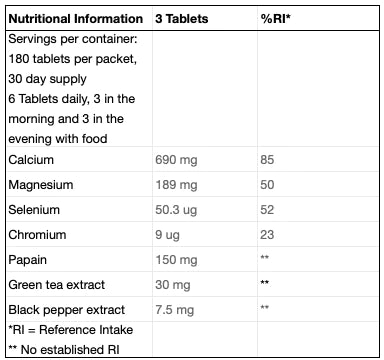

Adequate Rest and Nutrition: Speed work taxes the body more than steady-state endurance training. Ensure to get enough sleep and consume a diet rich in carbohydrates to fuel workouts, and protein to aid recovery.

-

Proper Technique: Finally, it's crucial to maintain good form during speed work. Poor technique not only reduces efficiency, but it can also increase the risk of injury.

Incorporating speed work into an endurance athlete's training regimen can significantly improve performance. It may seem counterintuitive for athletes who compete in long-distance events to focus on speed, but it's an investment that pays off. By enhancing aerobic and anaerobic capacity, neuromuscular efficiency, and running or cycling economy, speed work can help endurance athletes reach new performance heights.

Remember, though, speed work is a potent stimulus, and like any strong medicine, it must be used judiciously. Gradual incorporation, specificity, periodisation, active recovery, adequate rest and nutrition, and good technique are all vital to effectively up the ante with speed work. Incorporating these principles will allow endurance athletes to unlock the benefits of speed work