Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is characterised by fatigue that is disproportionate to the intensity of the effort undertaken and has persisted for six months or longer plus has no obvious cause.

Unless there has been a long period of athlete or doctor imposed inactivity, objective data may show little reduction in muscle strength or peak aerobic power, but the affected individual typically avoids heavy exercise.

The condition shows some similarities to overtraining and is a well recognised problem among high-performance athletes. CFS can and does develop in non-athletic individuals; however, there seem to be some points of difference from the syndrome as observed in athletes.

Assumed causes of CFS include the following:

1) Primary or secondary disorder of personality.

2) Anxiety and depression.

3) Nervous-system dysfunction.

4) Hormonal disturbances.

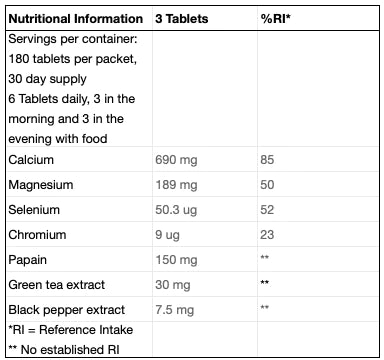

5) Nutritional deficits.

6) Immunosuppression and infection.

7) External factors - physical or emotional stress, overtraining, trauma, injury and high-altitude training.

In an athletic population it is often quite difficult to distinguish between a normal level of fatigue, overtraining (an inability to perform at a previously demonstrated optimum level despite a continuation of intensive training), fatigue that indicates the onset of some specific medical problem and CFS.

The apparent prevalence of the disorder and its characteristics depend largely on the criteria that are adopted for diagnosis and the specialisation of the examining doctor. For example, if an athlete with CFS is examined by a sports physician, it is likely that some evidence of overtraining will be reported. In the general population, there is substantial overlap between CFS and unexplained chronic fatigue. Other potentially overlapping conditions include fibromyalgia, Sjögren’s disease (an immunological disease) and depression.

The treatment of any form of CFS requires a holistic approach. Rest and regeneration strategies are central to recovery. Athletes hate to rest, but fortunately their drive to exercise can be channelled to help speed their recovery. Given that many of the manifestations of CFS are associated with a cessation of training and resultant de-conditioning, it seems logical to encourage the implementation of a carefully graded program of conditioning as a central component of treatment once any precipitant, such as infection or injury, has been resolved.

A moderate and progressive increase over current levels of exercise may help give the chronically fatigued athlete a sense of control over the condition. On the other hand, a sudden return to an excessive level of physical activity can exacerbate symptoms. Management is thus based on the principle of avoiding setbacks in recovery by appropriate control of the level of exertion. A careful recording of the frequency and intensity of physical activity and its correlation with self-reports of symptoms is sometimes helpful in setting an appropriate exercise prescription. Repetition of the activity should be avoided if the resting heart rate increases by more than 20 beats per minute.

Despite some progress over the past five years, many major issues remain to be resolved with regard to CFS. Is it one disease or many? In the case of the high-performance athlete, is there a clear linkage to overtraining, resulting immunosuppression and development of reactivation of infection? Most recent articles recommend a progressive exercise regimen as part of treatment, but there is still a need to define the optimal pattern of reconditioning. For example, it has been suggested that athletes with CFS should exercise aerobically, while sustaining a pulse rate of 120 to 140 beats per minute (such that they can easily conduct a conversation while exercising) for a few minutes (five to 10) each day, ideally in divided sessions, and slowly building up from there over many weeks.

At present, it appears that CFS must be categorised as a syndrome rather than a clear-cut disease, defined by a symptom-complex rather than clear physiological and biochemical manifestations. In the absence of a clear pathology, treatment remains unsatisfactory. In athletes in whom the condition has become established, the best advice seems to be to break the vicious cycle of effort avoidance (resulting in a decline in physical condition and a deterioration of morale) by a combination of encouragement and a carefully monitored progressive return to training.