Among your foremost needs as a triathlete is that of determining how to best allocate your energies within each discipline. Figuring out how much of every week's (or cycle's) training mileage should be dedicated to intense intervals and to longer, more sustained high-end efforts versus the amount that ought to consist of easy recovery running is something that can take years of trial and error. The right mix varies widely between individuals.

Triathletes, whose every session contributes something to their overall aerobic base, are more concerned with making the most of every run than with jogging around between hard workouts. With this idea in mind, it is sensible to approach run training through a scheme that is anchored on three basic types of key workouts: Long runs, medium-long runs and intervals.

The particular scheme that I employ with my athletes divides each type into three general subtypes. Medium-long and long runs are divided into steady-state, medium-paced and fast-paced subtypes. Intervals are divided into short-, medium- and long-interval subtypes. With one subtype of each type done each week, athletes complete one multi-pace training cycle that includes nine distinct workouts every 21 days before embarking on the next or tapering for an upcoming competition.

Overall running volume also fluctuates on a three-week cycle. Mileage is relatively lower in week one, medium in week two, and highest in week three.

Here's a glimpse at how this will ultimately look in schematic terms:

|

|

Mon. |

Tues. |

Wed. |

Thurs. |

Fri. |

Sat. |

Sun. |

Mileage |

|

Week 1 |

|

Medium-long run/fast finish |

|

|

Long intervals |

|

Long run/marathon pace |

Lower |

|

Week 2 |

|

Medium-long run/steady state |

|

|

Medium intervals |

|

Long run/fast finish |

Medium |

|

Week 3 |

|

Medium-long run/lactate threshold |

|

|

Short intervals |

|

Long run/steady state |

Higher |

These workouts will be described in detail in a series of three columns. This first installment deals with the workout of greatest interest to triathletes: The long run. Whether your aspirations center mainly on shorter events or you're aiming for an Ironman, long runs comprise the core of your perambulatory training.

Types of Long Runs

Steady-state. The main benefit of a standard, or steady-state, long run is furthering endurance and building a basic resistance to fatigue; not only fatigue incurred during competition but in the course of various other types of training. When done at about 70 percent to 75 percent of VO2max (or 75 percent to 80 percent of max HR), these runs increase the fuel-burning efficiency of both type I (oxidative) and type IIa (fast-oxidative) muscle fibers, and require less recovery time than more intense long bouts.

Pace is not a concern during these runs, so you're free to undertake them on trails and hillier courses. However, be aware that especially rough terrain that prevents you from maintaining smooth form throughout the run creates a suboptimal situation, as it's important – even more so for multisport athletes than for marathoners – to practice good form with steady turnover while tired.

A sample run for someone with Ironman experience and the ability to run 3:30 in an open marathon (8:00 pace) would be 18 to 22 miles at about a 9:00 to 9:30 pace, assuming good weather and a favorable training course. For specificity, it would make sense to do these the day after a long bike ride.

Fast finish.

Although it is a challenge to change gears after being on your feet for a couple of hours, the benefit lies mainly in calling into play type IIb (fast glycolytic) muscle fibers, goading them into assuming a more endurance-oriented character. In long events – particularly those in which the running component is at the end – it is vital to maximally train each fiber type in a way that allows it to contribute to long-distance performance. No matter what, your type I and type IIa fibers will always do the lion's share of the work in distance races, but by forcing your type IIb fibers to shoulder some of the load, you become a more economical and a more capable specimen overall.

A sample run for the athlete in the above example might be 16 to 18 miles, with the last two done at a pace starting at about 7:30 and dropping to 7:00 in the final three to five minutes.

Marathon pace. Mathematically, this type of long run is something of a compromise between the other two. It is also the most taxing, so ideally it should be performed at the end of an otherwise low-key week and not within three weeks of an important competition.

This run reinforces specificity of pace and effort. Although you won't come close to your fastest marathon at the end of an Ironman (or your fastest open 10K at the end of an Olympic-distance triathlon), it's still crucial to do a substantial amount of training at ideal marathon intensity so that the effort level is familiar to you during competition even if your pace is slower.

The amount of running to do at marathon pace varies according to your experience and the type of event. If you're aiming for an Ironman, you'll want to build up to runs of 16 miles that include around 12 miles at your optimal marathon pace, placed at the end of the run. Olympic-distance triathletes – almost all of whom will be racing, if not running, for well over two hours – should shoot for at least eight miles at marathon pace at the end of 14- to 16-milers. The slower portion of the run should be done at the same comfortable pace at which you do your steady-state long runs.

Putting It Together

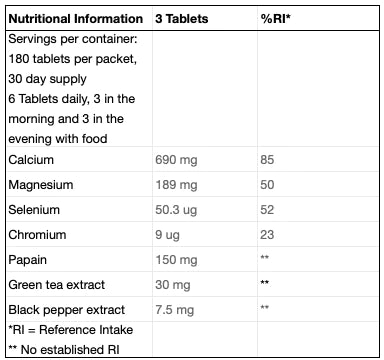

A training regimen that includes each of these types of long runs has you going long every week and rotating through each type. The basic, steady-state long run is the longest run you'll do in each cycle, the fast-finish run the second-longest, and the marathon pace run the shortest (although interchanging the latter two has never been known to kill anyone). So, in tabular form, our 3:30 candidate follows a plan like this one:

|

Week |

Distance |

Specs |

|

1 |

15 miles |

Last 6 miles in 48:00 |

|

2 |

17 miles |

Last 1.5 miles in 11:00 (7:30, 3:30) |

|

3 |

19 miles |

In 2:50:00 to 3:00:00 |

|

4 |

16 miles |

Last 9 miles in 1:12:00 |

|

5 |

18 miles |

Last 2 miles in 14:30 (7:25, 7:05) |

|

6 |

20 miles |

In 3:00:00 to 3:10:00 |